When we think about longevity in nature, few things capture our imagination quite like trees and plants that have stood for thousands of years. These botanical time capsules have witnessed the rise and fall of civilizations, survived dramatic climate shifts, and continue to thrive in some of the world’s most challenging environments. Their existence raises fascinating questions about survival, adaptation, and the incredible resilience of life on Earth.

Understanding Plant Longevity: What Makes These Organisms So Resilient?

Before diving into specific examples, it’s worth exploring what allows certain plants to achieve such remarkable lifespans. Unlike animals, many plants possess indeterminate growth patterns, meaning they can continue growing throughout their entire lives. This biological advantage, combined with other factors, creates the perfect recipe for extreme longevity.

Several key characteristics contribute to exceptional plant lifespans. First, many ancient trees exhibit incredibly slow growth rates, which helps them conserve precious resources and minimize metabolic stress. Second, these species have evolved remarkable environmental adaptations that allow them to thrive where other plants simply cannot survive. Third, many possess extraordinary regenerative capabilities, enabling them to produce new growth from existing root systems or damaged trunks. Finally, their dense wood structure often provides natural resistance to diseases, pests, and decay.

The Ancient Giants: Earth’s Oldest Individual Trees

1. Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva): The Champion of Longevity

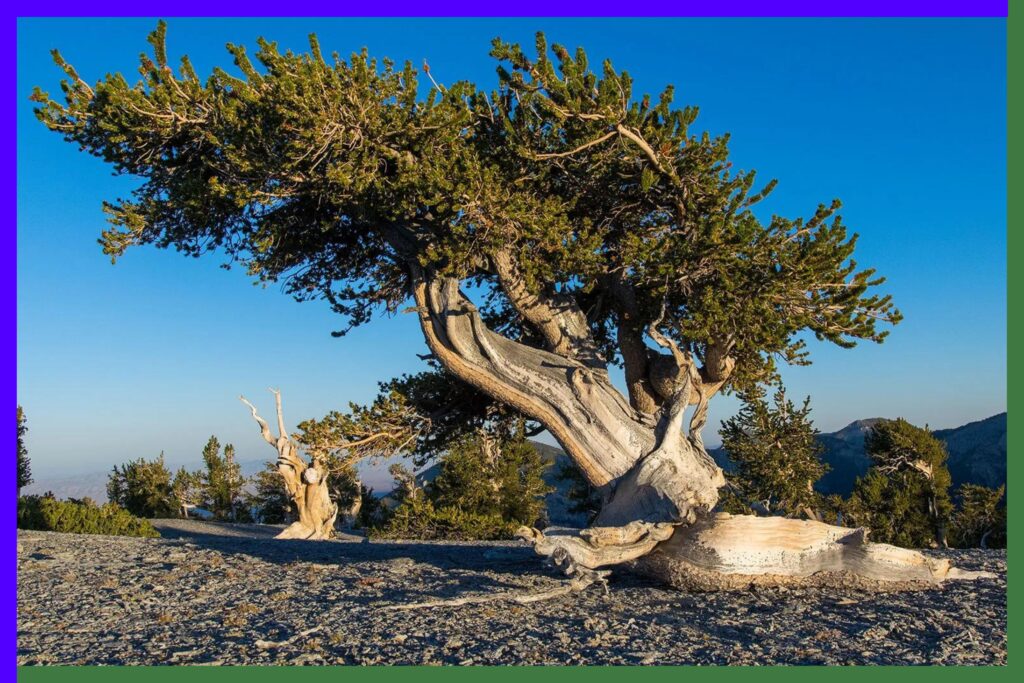

When discussing the world’s oldest living individual trees, the Bristlecone Pine deserves top billing. These remarkable conifers inhabit the harsh, windswept mountains of California, Nevada, and Utah, where they’ve mastered the art of survival in one of Earth’s most unforgiving environments.

What makes Bristlecone Pines so exceptional? Their secret lies in the very conditions that would kill most other trees. Growing at elevations between 9,800 and 11,000 feet, these trees endure freezing temperatures, intense UV radiation, and nutrient-poor dolomite soil.

The harsh environment severely limits their growth rate, with some trees adding less than one-hundredth of an inch in diameter per year. This glacial pace means their wood becomes incredibly dense and resinous, creating a natural defense against insects, fungi, and rot.

The twisted, gnarled appearance of Bristlecone Pines tells the story of their struggle against the elements. Wind and ice sculpt their forms, often leaving only a narrow strip of living bark connecting roots to foliage. This adaptation, called sectored architecture, allows portions of the tree to die while other sections continue living—a clever survival strategy that extends their lifespan far beyond what would otherwise be possible.

Individual Bristlecone Pines regularly exceed 5,000 years of age, making them the oldest known non-clonal organisms on the planet.

Clonal Colonies: Organisms That Challenge Our Definition of Individual Life

2. Pando: The Trembling Giant

While individual trees like Bristlecone Pines are impressive, some organisms achieve even greater ages through clonal reproduction. Pando, located in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest, represents one of the most mind-bending examples of longevity in the natural world.

Pando isn’t a single tree in the traditional sense. Rather, it’s a massive clonal colony of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) that shares a single, interconnected root system. Spanning over 106 acres and consisting of approximately 47,000 individual stems, this organism weighs an estimated 6,000 metric tons, making it one of the heaviest known living things on Earth.

What truly staggers the imagination is Pando’s estimated age: approximately 80,000 years. While individual stems typically live only 130 years before dying and being replaced, the root system has persisted since the last Ice Age. This ancient organism has survived dramatic climate changes, megafauna extinctions, and more recently, human development. Unfortunately, Pando now faces serious threats from overgrazing by deer and elk, which prevents new stems from maturing to replace dying ones.

3. Methuselah: The Ancient Witness

Among the Bristlecone Pines, one tree stands out for both its age and the mystery surrounding its exact location. The Methuselah Tree, named after the biblical patriarch who supposedly lived 969 years, is estimated to be approximately 4,850 years old. Located somewhere in California’s White Mountains within the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, its precise location is kept secret by the U.S. Forest Service to protect it from vandalism.

To put Methuselah’s age in perspective, this tree was already a sapling when the ancient Egyptians were building the pyramids. It has lived through the entire span of recorded human history, from the Bronze Age to our current digital era.

4. Old Tjikko: Survivor of the Ice Age

In the mountains of Sweden stands Old Tjikko, a Norway spruce (Picea abies) with a root system carbon-dated to approximately 9,560 years old. Like Pando, Old Tjikko achieves its remarkable age through clonal reproduction, with the ancient root system continuously producing new trunks.

The visible trunk of Old Tjikko is relatively young—perhaps only a few centuries old—but beneath the ground lies a root network that has survived since the end of the last glaciation. This tree has witnessed the entire span of human civilization, from hunter-gatherer societies through the agricultural revolution and into our modern technological age.

Ancient Trees from Around the Globe

5. Jomon Sugi: Japan’s Sacred Cedar

On the misty slopes of Yakushima Island in Japan grows Jomon Sugi, an enormous Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) whose exact age remains a subject of debate among scientists. Estimates range from a conservative 2,170 years to an extraordinary 7,200 years, making it potentially one of the oldest trees in Asia.

The name “Jomon Sugi” references the Jomon period of Japanese prehistory, suggesting the tree may have been standing when Japan’s ancient hunter-gatherer culture flourished. Today, this magnificent tree is protected as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and holds deep spiritual significance in Japanese culture. To prevent damage from the thousands of visitors it attracts annually, access is carefully controlled, and viewing platforms have been constructed at a respectful distance.

6. The Olive Tree of Vouves: Still Bearing Fruit After Millennia

On the Greek island of Crete stands an olive tree (Olea europaea) that may have been producing olives when the Minoan civilization was at its height. The Olive Tree of Vouves is estimated to be between 2,000 and 3,000 years old, though some local traditions claim it could be even older.

What makes this tree particularly remarkable is that it continues to produce olives to this day. Olive trees are renowned for their hardiness and ability to regenerate even after severe damage, drought, or fire. Their twisted trunks tell stories of survival, with new growth emerging from old wood in an endless cycle of renewal.

The Vouves olive tree has become a symbol of peace and longevity, with its branches used to create the olive wreaths awarded to winners at the Olympic Games held in Athens in 2004.

Remarkable Survivors in Extreme Environments

7. Welwitschia: Desert Marvel

In the harsh Namib Desert of Namibia and Angola grows one of the strangest and most resilient plants on Earth. Welwitschia mirabilis looks like something from an alien world, with only two leaves that grow continuously throughout its entire life, becoming tattered and split by the desert wind.

Some Welwitschia specimens are estimated to be over 2,000 years old, having survived in one of the driest environments on the planet. The plant’s deep taproot can extend over 100 feet underground to access moisture, while its two ever-growing leaves spread across the desert floor, sometimes extending over 20 feet in length.

This bizarre plant represents an evolutionary masterpiece of desert adaptation, able to extract moisture from fog and withstand years without rainfall—a testament to life’s ability to persist in even the most inhospitable conditions.

8. The Sacred Fig Tree (Ficus religiosa)

Known as the Bodhi Tree, this tree is sacred in Buddhist tradition, with some trees believed to be over 3,000 years old. One of the most famous Bodhi Trees is in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, and it has been cared for and protected for over 2,300 years.

- Location: Sri Lanka and India

- Spiritual Significance: The tree is highly revered in Buddhist culture as it is believed to be the site where Buddha attained enlightenment.

9. Baobab Trees: Africa’s Bottle Trees

The iconic baobab trees (Adansonia species) of Madagascar, mainland Africa, and Australia are among the most distinctive and long-lived trees in the world. With their massive, swollen trunks that can reach over 30 feet in diameter, baobabs store thousands of gallons of water, allowing them to survive severe droughts that would kill other trees.

Many baobabs are estimated to be over 2,000 years old, with some specimens potentially reaching 6,000 years. However, climate change has recently taken a tragic toll on these ancient giants. Several of Africa’s oldest and largest baobabs have died in recent years, a phenomenon scientists attribute to rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns.

Baobabs hold immense cultural significance throughout their range, often serving as gathering places, water sources, and landmarks for local communities. Their hollow trunks have been used as shelters, prisons, and even pubs in some locations.

10. Yew Trees: Guardians of Sacred Spaces

Throughout Europe, particularly in Britain and Ireland, ancient yew trees (Taxus baccata) stand sentinel in churchyards and sacred sites. These dark, brooding trees have long been associated with immortality, death, and rebirth—appropriate symbolism given their extraordinary lifespans.

The Fortingall Yew in Scotland is considered one of the oldest trees in Europe, with estimates of its age ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 years. Determining the precise age of yews is notoriously difficult because their trunks often become hollow with age, eliminating the growth rings that would allow for accurate dating.

Many yew trees were already ancient when Christianity arrived in Europe, and churches were often built near them, suggesting these sites held spiritual significance long before Christian times. The trees’ ability to regenerate new trunks from their roots and to send down aerial roots that form new stems contributes to their exceptional longevity.

India’s Ancient Botanical Heritage

India is home to several remarkably old trees that hold both botanical and cultural significance. While the Great Banyan Tree in Kolkata’s Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden is famous for its enormous canopy covering over 4 acres, other trees claim greater antiquity.

The Parijaat tree in Kintoor, Uttar Pradesh, is estimated to be approximately 793 years old. This tree holds special significance in Hindu mythology, where it’s described as one of the divine trees that emerged during the churning of the cosmic ocean. Local tradition maintains that the tree’s flowers only bloom at night and fall before dawn, though botanical records vary on this claim.

Read more – Fastest Growing Balcony Plants in India

The Baobab tree at Jhusi in Allahabad (now Prayagraj), estimated at 779 years old, represents one of the few baobab specimens found in India, likely introduced from Africa centuries ago. Both trees serve as living connections to India’s rich historical and cultural heritage.

The Science Behind Extreme Longevity

Modern research has revealed fascinating insights into how trees achieve such remarkable lifespans. Unlike animals, trees don’t experience aging in the same way. Their meristematic tissues—regions of actively dividing cells—can continue producing new growth indefinitely without the cellular senescence that limits animal lifespans.

Trees also benefit from modular growth patterns. If one branch or section dies, other parts continue functioning independently. This compartmentalization means trees don’t have a single point of failure; they can lose substantial portions of their structure while maintaining core life functions.

Additionally, many ancient trees produce antimicrobial compounds that protect them from pathogens. The heartwood of Bristlecone Pines, for example, is so resinous and dense that it can resist decomposition for thousands of years even after the tree dies.

Conservation Challenges and the Importance of Protection

Ancient trees face numerous threats in our rapidly changing world. Climate change poses perhaps the greatest danger, altering temperature and precipitation patterns that these trees have adapted to over millennia. The recent deaths of several ancient baobabs demonstrate how quickly these climate shifts can impact even the most resilient species.

Human activities also threaten these botanical treasures. Habitat destruction, pollution, tourism pressure, and in some cases, deliberate vandalism have all taken their toll. Even well-meaning visitors can damage ancient trees through soil compaction around roots or by touching bark surfaces.

These ancient organisms provide irreplaceable ecological services. They support countless other species, from lichens and mosses to birds and mammals. They sequester carbon, stabilize soils, and regulate water cycles. Their genetic material may hold keys to developing drought-resistant crops or understanding plant resilience.

Beyond their ecological value, ancient trees represent living connections to our past. They remind us of time scales beyond human lifespans and offer perspective on our place in the natural world. Protecting them isn’t just about preserving individual specimens—it’s about maintaining biodiversity, ecosystem health, and our planet’s natural heritage.

Protecting Our Living Monuments

The ancient trees and plants discussed in this article represent some of nature’s most remarkable achievements. From wind-battered Bristlecone Pines clinging to mountain slopes to the sprawling root system of Pando beneath a Utah forest, these organisms have mastered the art of survival across timescales that dwarf human civilization.

As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, these ancient beings offer both inspiration and warning. Their resilience demonstrates life’s incredible adaptability, yet the recent deaths of ancient baobabs remind us that even the most enduring organisms have limits. Protecting these natural wonders requires both local conservation efforts and global action on climate change.

By preserving these living connections to our past, we maintain not just individual trees, but entire ecosystems, scientific resources, and sources of wonder for future generations. In a world of rapid change, ancient trees stand as reminders that with the right conditions and protection, life can endure for millennia—a hopeful message for our planet’s future.

References and Further Reading

- U.S. Forest Service – Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest

- Smithsonian Magazine – “The Oldest Living Things in the World”

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – Tree of the Year

- National Geographic – Ancient Trees: